I am interested in those artists who attempt to find methods of escape and are committed to searching for it. Through art we can publicise our despair and dissatisfaction, emotions can be shown in their rawest form and we can once again express our imagination. I am intrigued by the Romantic Conceptualism movement, where the attributes of romanticism (feelings of alienation, solitude, unfulfilled longing, self-mutilation and melancholia) can charge a Concept,[2] bringing together sentimentality and subjectivity in an unlikely partnership. A luminary of this movement was Bas Jan Ader, who explored romanticism with a sense of irony. His work was always minimalistic, and simple, mostly using himself and the force of gravity as his medium.

In his film ‘I’m too sad to tell you.’ we experience a close up of Ader weeping, the action feels absolutely genuine, regardless of it being staged for camera. It is important for us to know that he is crying due to grief; there is a reason for his melancholy which he cannot express. The audience can barely speculate as there is no narrative, we are drawn into the isolated concept of sadness, in a similar way to Andy Warhol’s, ‘The kiss,’ which exemplifies the idea of lust. It is strange to describe a piece of work as abstract and personal, theatrical but genuine,[3] however Ader achieves this. The piece is relatable to the audience whilst remaining ambiguous. We are not invited in, and there is no narrative to react to. We are reminded of the loneliness of our individual souls, and our difficulties in expressing emotion. When read alongside ‘Fall 1,’ and ‘the artist as a consumer of extreme comfort,’ Ader’s works feel like allegories for melodrama and melancholia. Whilst Ader, ‘The artist,’ remains as the subject matter, he becomes a symbol of the hopeless romantic, constantly scanning the horizon for the sublime.

At the time of creating these works, Ader was entrenched within the conceptual movement in the heart of America. His work proceeded the writings of Sol Le Hewitt who reduced all sentimentality from his work in favour of rationalising the illogical, ‘It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with conceptual art to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually would want it to be emotionally dry,’[4] Within this context, Ader’s isolation of the ‘romantic,’ within his work, (including the kitsch aesthetic of pieces such as ‘Farewell to Faraway friends,’ which eludes to novelty postcards of sunset lit seascapes,) subjectifies the emotion, bringing the idea of romance and concept together innovatively. Romantic Conceptualism therefore becomes a possibility.

‘Farewell to Faraway Friends’ Bas Jan Ader, 1971

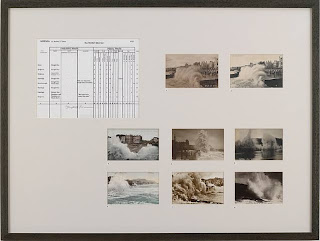

Susan Hillier worked parallel to Ader, her piece ‘Dedicated to the Unknown Artists,’ was scorned in its time, embracing the sentimentality of postcards specifically entitled ‘Rough Sea,’ and their kitsch representation of genuine artworks and emotive scenes. She too was misunderstood, accused of mixing pop art with conceptualism.[5] Within popular culture, postcards have become motifs for a more domestic notion of the sublime. Presenting these oversaturated depictions of British bays within a grid-like display, removes them from their original context, exposing their emotional cliché, whilst remaining conceptual. Here we can question the generic nostalgia pinned to them and the authenticity of the idyllic reproductions. Within my own work, I have undergone a battle against sentimentality, with its feminine connotations and twee aesthetics. It is only when sentiment is reduced to its purest form that it can be looked at conceptually. I wish to isolate the theme of escapism, paring the desire down to a minimalistic symbol of ‘an escape.’

‘Dedicated to Unknown Artists’, Susan Hiller, 1972

Within reality, escape and Utopia do not exist. Utopia is a Greek derivative, evolving from the conjunctives oύ, meaning "not" and τόπος meaning "place.” Originally our English word for this was eutopia, again deriving from Greek; it is translated as ‘good place.’ This homophone creates an interesting question, can Utopia exist? If you can escape from your reality, how long does this state of escape last for?

Ader left Holland to ‘find himself’ as an artist in Los Angeles; however the echo of his homeland haunted his practise and his soul. He was forever unsettled, his work was consistently rejected by his Dutch comrades and he found himself continuously hunting for the sublime, an obsession with discovering what lay over the horizon. The ocean and water are often present within his work, the ocean symbolizing the suffering traveller, discovery and solitude. His final piece of work, ‘In Search of the Miraculous,’ epitomized this yearning for fulfilment and escape. He sets sail from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA to Lands’ End, Britain in a tiny sailboat named, ‘Ocean Wave,’ returning home to Europe in the same manner as he arrived, objectifying the idea of a tragic romantic hero.

During this piece, Ader vanished at sea, achieving the unspoken desire to escape into myth. [6]The physicality of the ocean results in traceless disappearances, assigning a legendary status to those who cease to exist past the horizon. One matter of extreme importance was the discovery of the book, ‘The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst,’ within Ader’s locker. Con man Crowhurst had previously attempted to achieve the impossible by completing a single handed and non-stop round the world boat race. His creation of false diary logs, and fabricated positions in hope of gaining a fraudulent victory were swallowed up by his surroundings and his watery prison sent him insane. Just like Ader, all that was left to evidence his existence was his boat. It leads me to ask, could Ader’s destination ever have been home? He was not searching for the familiar, or for comfort but for the unknown, for the great and divine.

It is the relationship between the familiar and the unknown, reality and fiction which provokes a human desire to search for the miraculous. Through the blurred line between drifting into sleep and remaining fully conscious we can find ourselves in a strange state of being which is still unexplained. It feels familiar, yet it is extraordinary. We float within a zone of sentience rather than full consciousness. The scientific name for this area of being is ‘Hypnagogia,’ a sensation that has been explored by philosophers and scientists over the course of centuries. Within a hypnagogic state we can experience colour flares, nonsensical sentences, floating sensations and cloud like forms known as ‘entoptic lights.[7]’ which swamp our sensory system.

Acquiring this state has become an obsession for many. Brion Gysin’s dreamachine is said to allude to hypnogogia, forming dreamlike afflictions which are ordinarily only possible when falling into slumber. The originally cylindrical dreamachine pulsates light whilst the ‘viewer,’ closes their

eyes - the electrical oscillations triggered within the brain by the pulsations is supposedly similar to the human brain relaxing and drifting off to sleep. The hypnagogic state is, in a sense a collection of sublime physical, auditory and visual sensations, it is greater than us. It is intangible and unknown. It could be described as another state of reality, one that we have found a portal to and one that we cannot remain in.

What fascinates me about this state is the overwhelming intensity of these sensations. We escape from them by opening our eyes and returning to our familiar, comforting reality, which leads me to question ‘Where does the miraculous exist?’ Which, the dream or our reality, is the escape?

Within Ader’s practise, the ‘miraculous,’ was an intangible concept, he placed himself at the mercy of gravity and nature and was consumed by their vastness. ‘While you sleep a person turns inwards, our mind may roam far beyond the physical location of our sleeping bodies. We visit amazing realms, have miraculous experiences and are provided with sudden insights, like this planet keeps us bound to the earth with its gravity, preventing us from getting lost in the infinity of the cosmos.’[8]

This quote from J.A. Ader- Appels, Ader’s mother, is woven within his works. Her own research and studies into gravity influenced Ader greatly, inspiring him to use it as his medium. The moment between composure and falling, embodied his practise. He described this split second as ‘gravity making itself master over me.’ He was succumbing to a greater force. Hypnagogia, gravity and the cosmos exist as unfathomable pulls within the fabric of reality. As we each fall through time, space or consciousness we gain momentary escape from our everyday restrictions and embrace the bends existing within the norm.

The miraculous takes place outside our conscious being, surrounding us, invisible and just out of reach. Yet we can take solace in its existence and in the chance that we too, may fall into it.

J. Roberts and C. Schorr. 1994. Bas Jan Ader, Frieze magazine, (online) Available at <http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/bas_jan_ader/> [accessed 13th February 2011]

T.Dean, He Fell into The Sea, (online) Availiable at <http://www.basjanader.com/dp/Dean.pdf>[Accessed 19th February]

Edited by R.Noble, (2008) Utopias (Documents of Contemporary Art) London: The MIT press

B. Fer, R. Carvajal, T. Dean (2007) Tacita Dean Film Works, Charta publishing.

Daniel Albright (1981). Representation and the imagination. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p150 - p208.

Y.Klein Truth becomes Reality (1961) The Sublime. London: The MIT Press

O.Eliasson The Weather Forecast and Now (2001) The Sublime. London: The MIT Press

J.Lyotard Presenting the Unpresentable (1999) The Sublime. London: The MIT Press

J.Verwoert, S. Hiller, J. Heiser, C. Schorr (2008) Romantic Conceptualism, Nurnberg: Kerber

A.Gallagher, (2011) Susan Hiller, London: Tate publishing

J.Verwoert (2006) Bas Jan Ader, In search of the Miraculous, Cambridge: The MIT Press

A.Mavromatis, Hypnagogia (2010) The unique state of conciousness between wakefullness and sleep, Thyros Press

J.A. Ader (1947) Een Groninger Pastorie in de Storm, Netherlands:Pressure 13

J.Hobson (2002) Dreaming, a Very Short Introduction, New York: Oxford University Press

D.Coxhead, S.Hiller (1976)Visions of the Night, Dreams, New york: Thames and Hudson Inc

Z.Felix, I. Kabakov (2000) The Text as a Basis of Visual Expression, Hamburg: Oktagon

R.Rugoff, S.Rosenthal, M.Katoka,S.Blackmore,H.Luckett,B.Dillon(2009) Walking in My Mind, London: Hayward Gallery

Sol Le Witt, (1967) ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,' Art Forum,pp79-84

Here is Always Somewhere Else (2008) DVD, Rene Daalder, Cult Epics

[1] THOUGHTS UNSAID THEN FORGOTTON,(1973) oil slick, tripod, clamp on lamp, flower, vase. (installation)

[2] J.Heiser, Emotional Rescue, Frieze, available; http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/emotional_rescue/ accessed 2 February 2010

[3] J.Heiser, Emotional Rescue, Frieze, available; http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/emotional_rescue/ accessed 2 February 2010

[4] Sol Le Witt, (1967) ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,' Art Forum,pp79-84

[5] J. Heiser, J.Verwoert with S.Hillier,(2007) Susan Hillier-3512 words, Romantic Conceptualism, pp51-155